A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit mind activity wirelessly for extended durations.

Researchers at Cornell University, operating with collaborators, have formed a really small neural implant which could take a seat on a grain of salt even as wirelessly sending brain activity data from a living animal for more than a year.

The advance, reported in Nature Electronics, shows that microelectronic systems can function at a scale smaller than formerly feasible. This achievement opens the door to latest tactics in long-term neural tracking, bio-incorporated sensors, and related technologies.

Shrinking neural implants to the extreme

The device, known as a microscale optoelectronic tether less electrode, or MOTE, was developed beneath the joint leadership of Alyosha Molnar, a professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Cornell, and Sunwoo Lee, an assistant professor at Nanyang Technological University.

Lee start working on the technology earlier as a postdoctoral researcher in Molnar’s laboratory.

Wireless power and optical data transfer

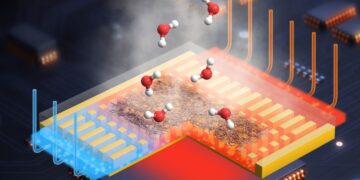

The MOTE is powered by red and infrared laser light which could safely pass through brain tissue. It sends information back through emitting brief pulses of infrared light that deliver encoded electrical signals from the brain.

A semiconductor diode crafted from aluminum gallium arsenide harvests the incoming light to power the circuit and also gives the outgoing signal. The system is assisted by a low noise amplifier and an optical encoder, both built with the equal semiconductor technology particularly utilized in modern microchips.

The MOTE is about 300 microns long and 70 microns wide.

“As far as we know, that is the smallest neural implant so that it will measure electrical activity in the brain after which report it out wirelessly,” Molnar stated. “By using pulse role modulation for the code – the same code utilized in optical communications for satellites, as an example – we can use very, very little power to communicate and nonetheless successfully get the data back out optically.”

New opportunities for brain and body tracking

The researchers tested the MOTE first in cell cultures and then implanted it into mice’s barrel cortex, the brain region that tactics sensory information from whiskers. Over the time of a year, the implant successfully recorded spikes of electrical activity from neurons as well as broader styles of synaptic activity– all whilst the mice remained healthy and active.

“One of the motivations for doing this is that traditional electrodes and optical fibers can irritate the mind,” Molnar stated. “The tissue moves across the implant and can trigger an immune reaction. Our aim was into to make the device small sufficient to minimize that disruption while still capturing brain activity faster than imaging systems, and without the need to genetically regulate the neurons for imaging.”

Molnar stated the MOTE’s material composition could make it viable to collect electric recordings from the brain at some point of MRI scans, which is basically not possible with recent implants. The technology could also be adapted for use in other tissues, together with the spinal cord, and even paired with future innovations like opto-electronics embedded in artificial skull plates.

Molnar first conceived of the MOTE in 2001, but the research didn’t gain momentum until he started out discussing the concept about 10 years ago with members of Cornell Neurotech, a joint initiative between the College of Arts and Sciences and Cornell Engineering.